“...she kept her eyes on the rack in front of her, filled with spikes and live filaments on which she tested each bulb. The good ones she put in their individual hole in the tray on her left, the duds in a basket by her right knee. It was clean work, the factory was quiet enough to hear the wireless, and it paid better than the Tin Can Works.“

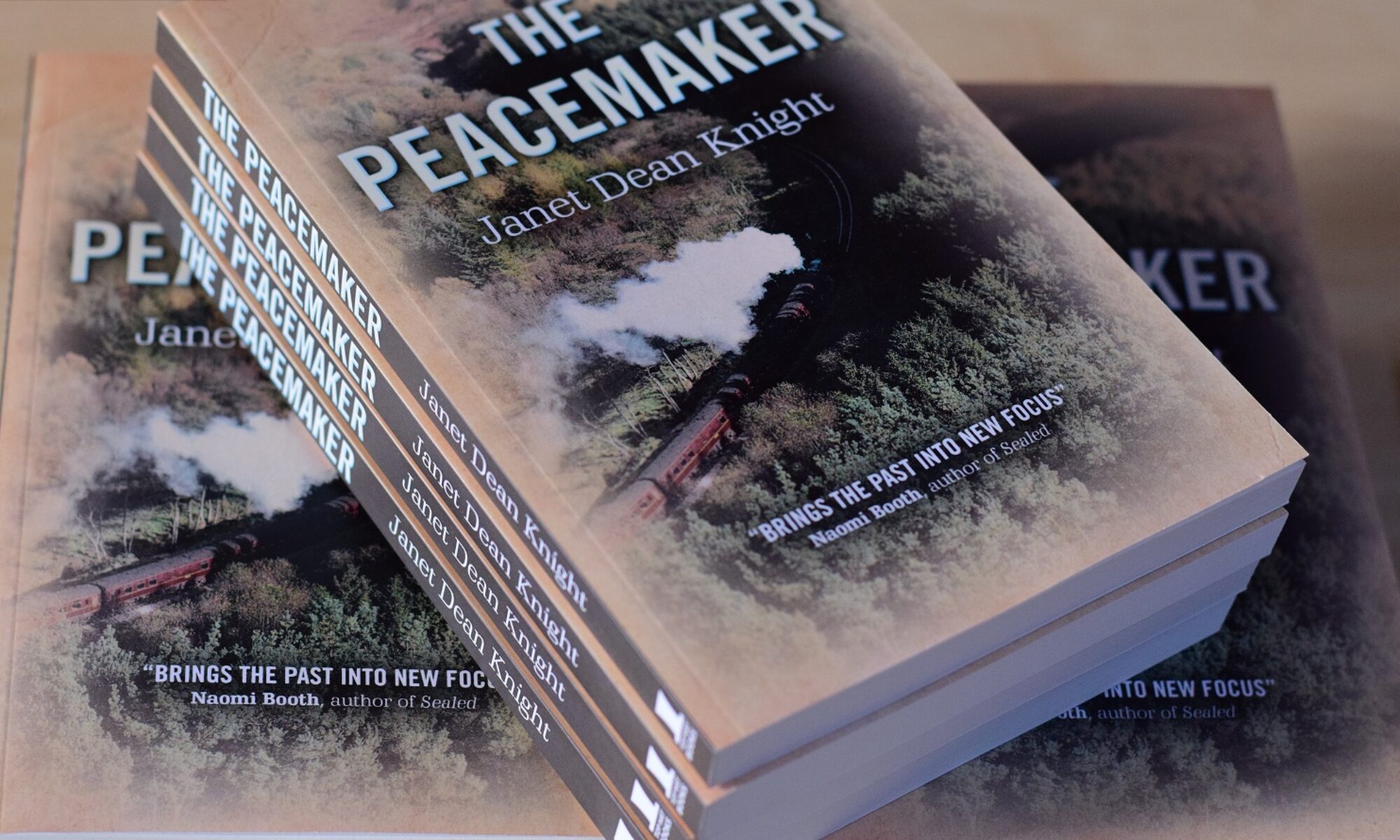

The opening scene in my novel The Peacemaker is based on this still from a short film which I found in the Yorkshire Film Archive. It is a glass factory – the CEAG Factory in Barnsley, South Yorkshire – famous for making miners’ lamps and light bulbs. My book is fiction, but based on fact. The main character, Violet Lowther, is based on my mother aged 18. She never worked at CEAG, but she worked in other factories and I grew up knowing people who worked there.

Our lives are made up of stories, and they blend fact and fiction. Just before I was 18, things changed for me in a way which has affected the whole of my life – I had my first experience of depression. One summer day I walked to school as usual, but I felt very sad. I sat in the sixth form common room feeling as if I were in some kind of bubble, set apart from everybody else. And then somebody spoke to me. I couldn’t answer; I burst into tears and ran off to hide in the cloakroom.

In the month that I needed to recover enough to go back to school, my mother cared for me in a state of bewilderment – at a loss to understand why I had gone from being a happy teenager to a distraught young woman. She seemed puzzled but she never criticized me or tried to get me to shake off my mood. She took me seriously, got me treated by a doctor and with her help I came through that episode.

Most people who know me think of me as positive, an extrovert. I laugh a lot and generally come across as a jolly type. But I have been treated for depression about twelve times in my life, always with medication, occasionally with counselling. The story I present to the world is a happy one, but I sometimes mask a deep sadness inside.

I have seen this pattern occur in my family, and in researching deceased relatives as background to The Peacemaker, I could see that many of us have shared an experience of mental ill health which we have managed in different ways, sometimes by medicating ourselves, often with alcohol.

What is difficult to see is cause and effect. Is our experience of mental health an inherited trait? Or are we responding to events in our lives which destabilize us? Perhaps both. The concurrence of trauma and economic or social distress with mental ill health is very strong, but not everybody who experiences physical pain, poverty or discrimination reacts the same way. Sometimes my depression has coincided with difficult life events – the death of my parents, the post-natal depression after the birth of one of my children – but at other times it has seemed to come from nowhere. Sometimes I have dealt with difficulty by facing it head on and pushing through, at other times by needing to retreat for a while. There is no right or wrong. I might catch a cold or I might not, I might have a heart attack or I might not. There are a lot of variables, physical and environmental.

We continue to ask: see mental health like physical health – it is all health. We can help ourselves to be healthy, but sometimes we will become ill, no matter what we do, whoever we are. If we live happy, prosperous peaceful lives, our health will be generally better. As I saw from the generations of my own family who experienced poverty and war decade upon decade, from one century to another, their health suffered both in body and mind.

We know we inherit predispositions to physical ill health, and we may to mental ill health. We also know how important our environmental, economic and social circumstances are in keeping us healthy. In Mental Health Awareness Week, on World Mental Health Day, let’s all watch out for each other.