I have many pictures of my daughter and myself and I love them all, but they really do remind me how old I am!

Youth is the gift of nature, but age is a work of art‘ Stanislaw Jerzy Lec

In the month that I reached 65 (but without the consolation of my state pension), I am comforted by the words of Polish poet Stanislaw Jerzy Lec. I intend to see myself as a work of art from now on.

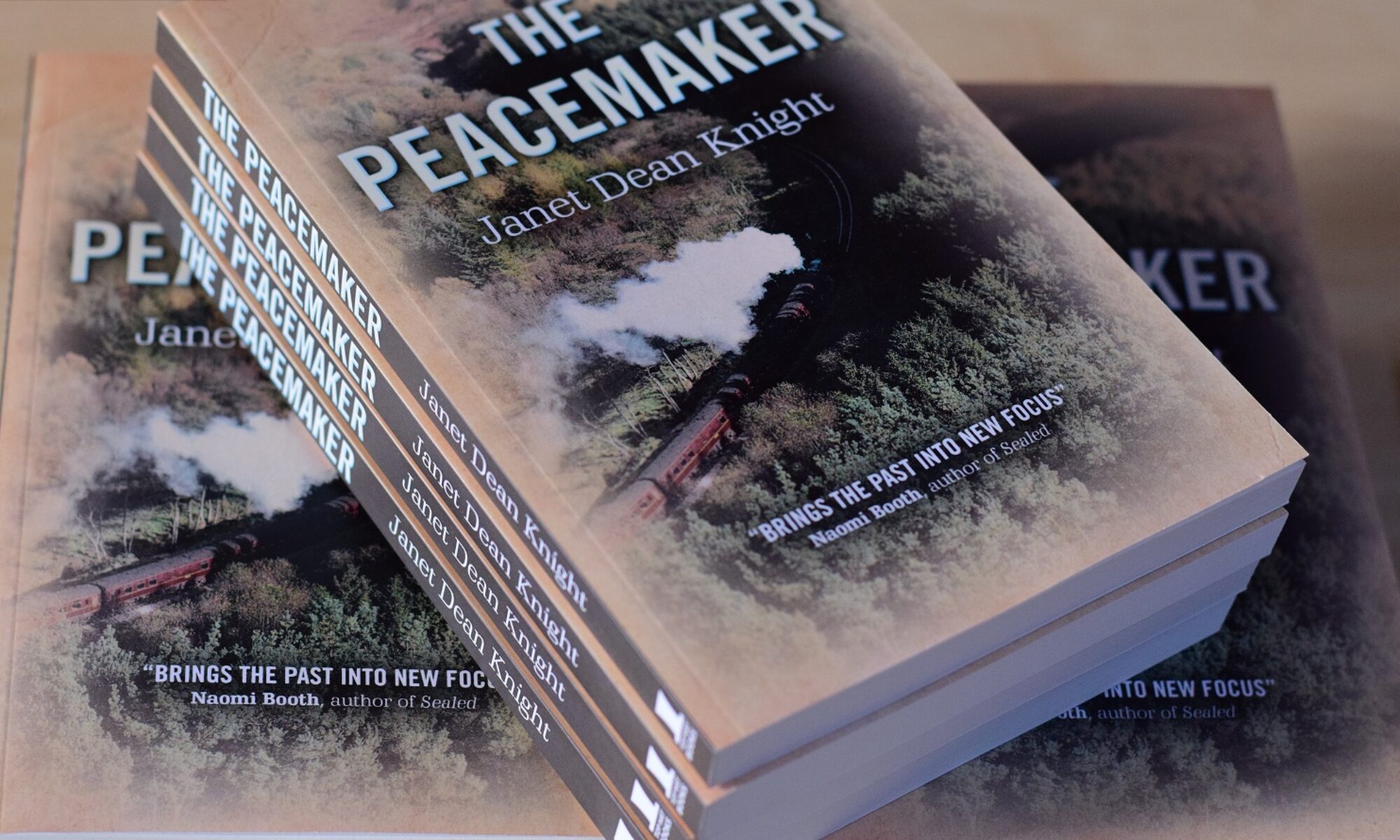

A year has gone by since the first wave of coronavirus. It has felt like a year on hold in a lot of ways – mostly in relation to seeing friends, travelling, and enjoying live events – but for me it has also been a year of great progress.

I have made progress in writing, a lot of progress when I think about it. I had completed a first draft of my second book Does She Love Us? by December 2019, but during 2020 I had some fantastic advice and feedback on that draft and made some major structural edits and revisions which I completed by December 2020. I think the book is now finished and I am actively looking for the right publisher to bring it into the world, with several options under consideration. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the different routes to publishing, both traditional and independent, especially if you’ve got experience of one or other or both.

I was very lucky this week to have the chance to talk to writer and musician Miles Salter about Does She Love Us? The book is set in 1963 and is about the lives of working-class women in a northern mining village. In International Women’s Week we talked about how things were different for me and my mother, and how they are different for my daughter. There has been a lot of change, but in some areas, just not enough. Women are still fighting for equal treatment in terms of pay and status at work, they are still battling against misogyny and assault, and they still experience discrimination economically and in terms of health, as emerging studies about the effects of the pandemic are showing.

In my novel, I deal with legal and economic inequality, constraints within marriage, lack of contraception and illegal abortion, issues which were not the same for me, thank goodness, but even today many women are still engaged in daily struggles because of poverty, poor health and social discrimination. If you’d like to hear me talk about the book, you can listen again by clicking here. The programme was broadcast on Wednesday 10th March.

As I’ve said before, I found writing and reading fiction hard last year, but I did make a start on my third book, provisionally called The Man in the Street Had No Shoes. I’m about a quarter in, and need to crack on with it, because I’m already starting to play around with the structure, and I need words on paper to do that properly. I made most progress with poetry and have produced about 40 new poems and revised a whole lot more. I am looking forward to some of these making their way into pamphlets or being published in print or online this year.

One of the good things about 2021 is being able to read fiction again. So far my reading list has been dominated by prize-winning women writers – Maggie O’Farrell’s wonderful but tragic Hamnet, Bernardine Evaristo’s delightfully wide-ranging Girl, Woman, Other and Anne Enright’s challenging and disturbing The Gathering. I’ve just started tackling Hilary Mantel’s momentous The Mirror and the Light which I know will be an immersive experience.

Coming back to the matter of age, it was interesting to see Bernardine Evaristo’s observation that there were no older women on the recently announced Women’s Prize for Fiction longlist. Although one or two are in their sixties, she was particularly highlighting the absence of women in their seventies and eighties, and really speculating whether they disappear at that point. Men don’t, as a nearby article on Richard Murdoch at 90 illustrated. I hope women over 60 don’t disappear – I for one have got so much more to do!

With best wishes to you all!