I started 2020 full of optimism and good intention. I wrote blogs in January and February and sent out newsletters, hoping that this would be a year where I kept in touch more with readers. But the world was changing, and in March the UK became a different place.

My birthday is in early March and I had gone with my family to spend a few days on the beautiful Northumberland coast. That weekend the first deaths from Covid-19 were recorded in the UK. On the 13th March I met a friend for lunch, the last time I did so, and only now is that possibility returning. Our daughter called in that evening after work, and didn’t visit again until May when we could socially distance in the garden. We are just having the odd couple of friends round now, but we won’t be returning to foreign travel, restaurants, pubs or cinema for the foreseeable future, even if it is allowed.

The change to internet deliveries and local specialist shopping is a permanent one, I think, and as I look back over the spring and early summer, Lockdown has left our family with a lot of positives as well as some sacrifices. We have a lovely walled garden which is unusual close to the centre of York, and we have turned some of it over to growing potatoes, onions, tomatoes, lettuce, strawberries and herbs. We bought a beehive and bees were delivered at the end of April, and after half the hive split off and were recaptured we now have two hives! The garden is full of perennials and wildflowers, different varieties of bees, butterflies, insects and birds. In the silent early days of Lockdown the song of the blackbirds and robins was a real treat, as was the glorious April and May weather.

What have you been doing in Lockdown – what will you keep and what will you be glad to see the back of?

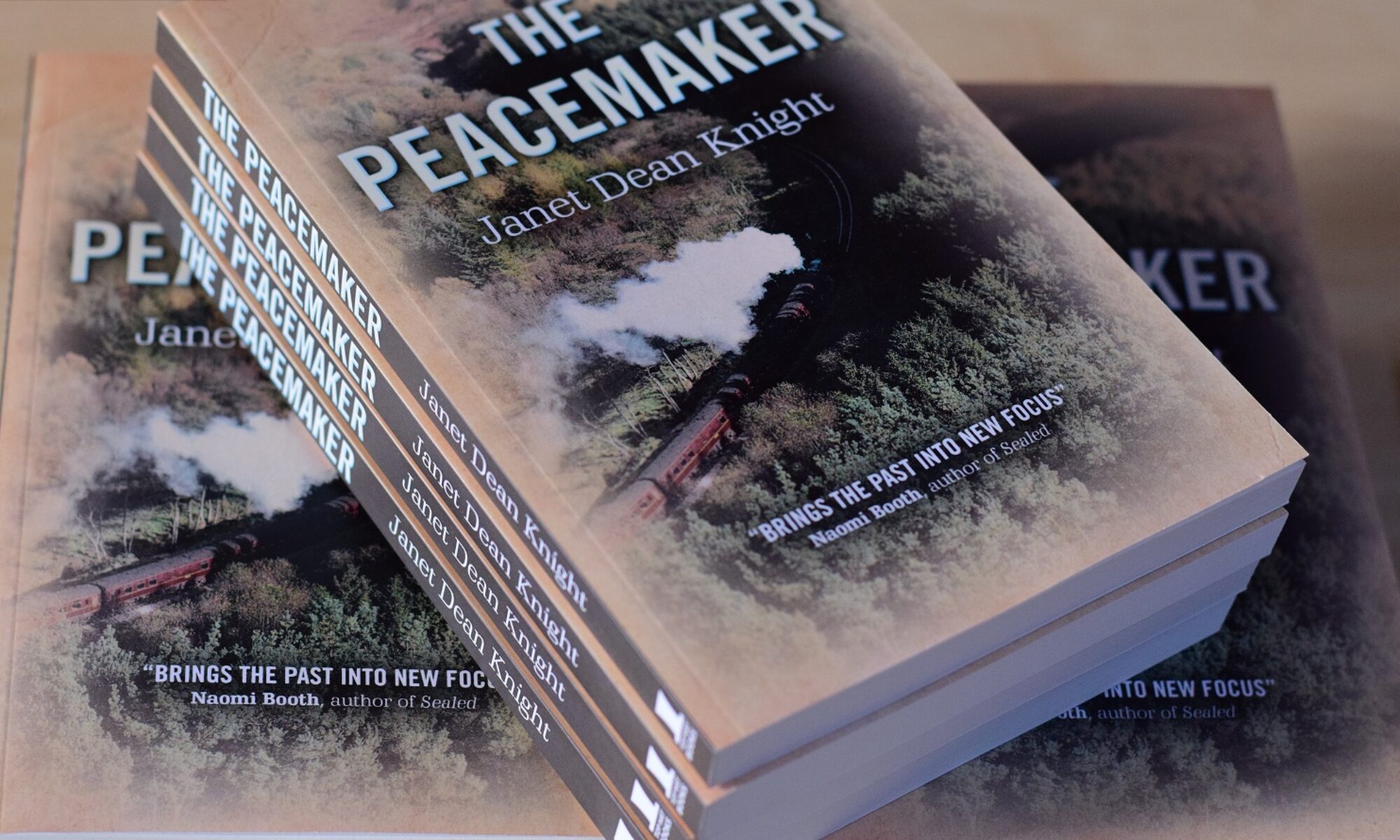

There has been much talk about the pandemic being our generation’s challenge equivalent to wartime, with comparisons to the numbers of people killed in the Blitz. Having written in The Peacemaker about that tense time as war was looming, we have certainly had to adjust to widespread fear, difficulties getting food and strains on public services, but our lives now seem much more complex and the current challenge is navigating a return to normal whilst the threat of coronavirus still lurks in our midst.

Reader’s Block/Writer’s Block

Some people have found the space of lockdown ideal for reading and writing. Others haven’t had any space as they tried to juggle home schooling or community service with work or caring responsibilities. Some of us have been stuck, probably because our heads were filled for a time with daily briefings and the appalling rise in cases of Covid-19, and tragically, deaths.

I have found it hard to work on my second book, Does She Love Us? so in March, April and May concentrated on sending it out to agents and publishers. In April, which was NaPoWriMo (National Poetry Writing Month) I did a month long course with a daily writing prompt and had some mentoring support from a well known poet who helped me put a new poetry pamphlet together. I started work on a new novel about a woman who meets a homeless man and realises he is the person she almost married 30 years before – it’s called Whatever Happened to Oliver Cartwright? and I’m quite excited about it.

In June I got some editorial advice about Does She Love Us? which has re-energised me to get stuck into refocusing the novel to make it as good as I believe it can be. I’m also reading more – mostly poetry – having struggled to read anything but news for weeks, so I’m hopeful that my new normal will mean more words either written or read. This blog is a start!

A Virtual World

Events to promote The Peacemaker were cancelled in March, but I had the pleasure of presenting to 80 people via Zoom as part of the #StayAtHomeFestival. I am missing meeting book groups, particularly, and would be delighted to do them via Zoom if any of your groups have transferred to that platform. Just get in touch.

On my courses and events page you’ll see how Awakening The Writer Within has been affected by Covid-19. It is sad not to be with people, but wonderful to be able to reach so many more – do join us if you would like some inspiration to help you write – it works for me!

To whet your appetite, here’s a little taster adapted from our workshop on the 4th July.

Shopping Day:

It’s 2030, shops are still operating but are completely contactless and transactions are done by face recognition. You go to buy something in your favourite store, but the system doesn’t recognise you. You don’t seem to exist.

Write a piece of flash fiction (under 500 words), a poem or short drama in response to this prompt.

Very best wishes to you all

Janet